robot reveals

Unpacking first impressions of physical autonomy, ft. Bittle by Petoi

This research began at UT Austin - read the thesis report here

-

I think designed introductions to physical autonomy are on the critical path to the most beneficial adoption of mobile robots into applied environments. By presenting these prototypes to students on campus, I was able to investigate how people responded to sharing space with a robot - and the influence of different packaged contexts.

-

Some Context >>>

Physical autonomy can elicit strange, visceral responses, or:

“Robots, when they move around with ‘purpose,’ elicit an inordinate amount of projection from the humans they encounter” -Kate Darling, PhD.

Film loves a robot reveal: Blade Runner 2049 No One Dies From Love - Tove Lo Automation Be Right Back - Black Mirror The Gift Big Hero 6 Robot Dreams ...and robots have a long history with fiction

By way of analogy, think of how Apple & Ridley Scott’s 1984 advertisement engaged with existing fiction narratives to introduce a new machine.

Real unboxings are varied in flavor: Aibo Furby Roomba Astro PAL Spot Go2 Nao Figure Eilik EMO Moxie

Some of the existing design language around this moment, in form of fictional and real reveal moments, side by side:

Interestingly, companion robots like the Sony Aibo (“cocoon”case), Eilik (“Welcome aboard!”) Furby (“Keep out! Furby and Bestie only”) use zoomorphic & anthropomorphic language, seemingly, to facilitate projection. This led me to wonder how else packaging elements could be used - e.g. to encourage or discourage projection.

|| Recommendations

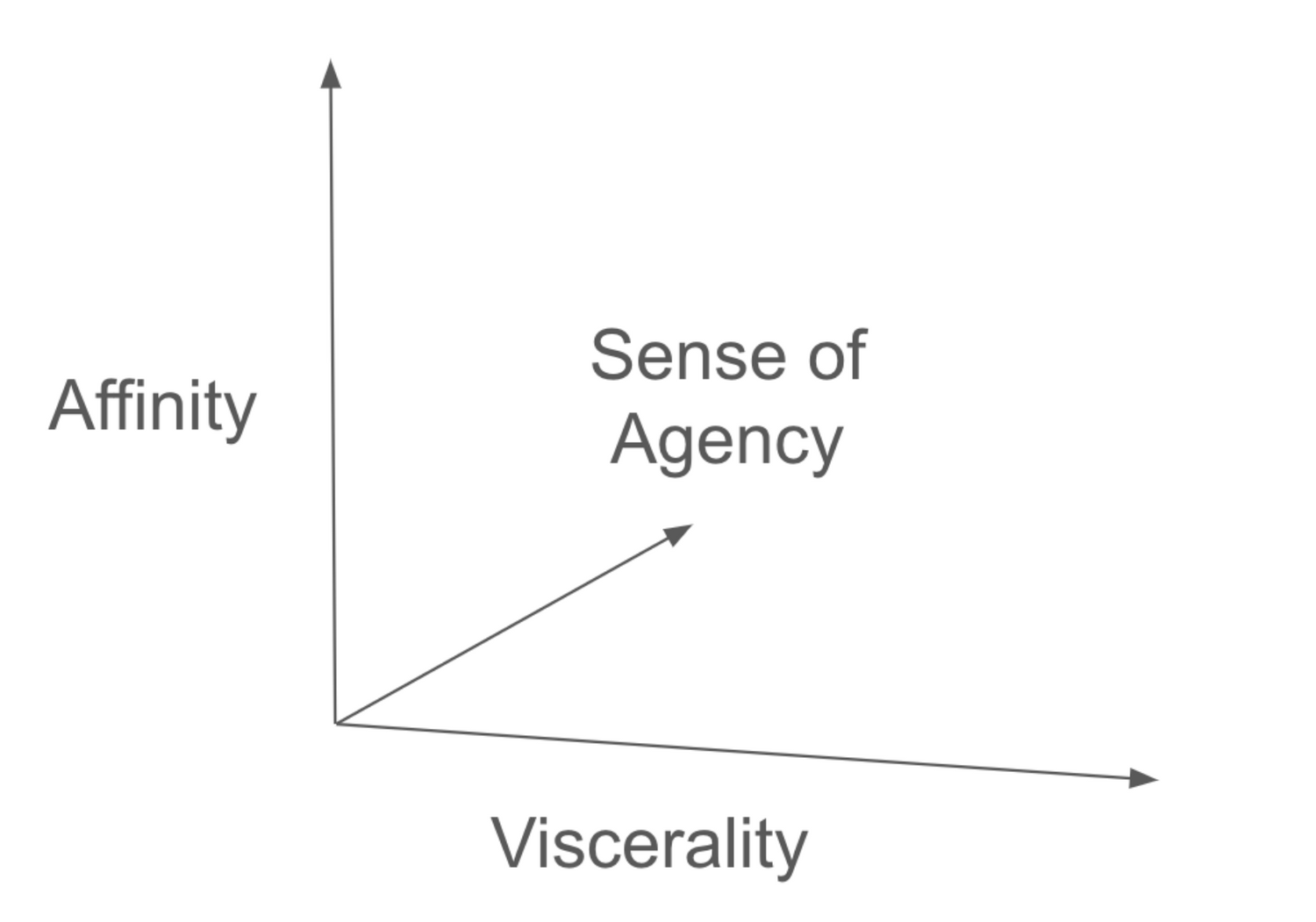

Know your user and know your goal: what is your user’s default inclination towards robots? Do they like them? Do they react viscerally or not? What reaction is beneficial for first-contact given the robot and use case? Where will your process of introduction nudge them?

Provide a sense of craft: A sense of craft was appreciated accross user types. This is, perhaps, unsurprising when speaking with design and information students. However, affinity varied dramatically for some users between prototypes that involved motion (provolking unease) and prototypes that were more static. Users without visceral reactions were sometimes bored by prototypes that others found alarming or delightful (or both). Yet, both emergent categories appreciated a sense of quality, attention to detail, and the use of seeminlgy novel or valuable materials.

Soft materials elicited gentler interaction and implied a sense of fragility, lowering initial expectations of the product. Given Takayama’s 2010 study on expectations and the addage ‘customer satisfaction = expectations - results’ this may be useful in nudging users to start slow, while setting them up for rewarding subsequent interactions. Soft materials were also ‘unexpected’ by many users, though pleasantly so.

Be cautious with biomimetic packaging or introductions: Overly lifelike design elements can elicit uncomfortable reactions. Use them carefully, especially if your user tends to react viscerally to robots. Symbolic biomemisis - i.e. cases where the representation was recognized, but not viscerally - was received more positively. Users disinclined to visceral reactions with robots (e.g. more ‘jaded’ users, perhaps due to prior interaction with similar systems) were relatively uninfluenced by biomimetic attributes, including visible form of packaging or the use of motion. However, users with more visceral reactions reacted strongly, and in a manner more difficult to predict, when presented with biomimetic motion or forms.

Foreground user control and dependencies: present controls or method of interfacing upfront to alleviate anxiety around autonomous functions: a remote, perhaps a power button, a charger or power supply. Given popular fiction and narratives, these can serve as opportunities to remind the users of their agency in relationship to the machine.

Provide users context before motion: when motion preceded visibility of robot form, users reacted with unease. When concurrent, less so. When users held a remote before encountering a static robot form, reactions were the least volatile. Precede user encounters with motion with information about context and control.

Include robot ‘stumbles’: including fumbling erros may make a robot more relatable and less intimidating, while quickly showcasing both limitations and capabilities (e.g. recovery).

|| Spicy takes (newfound opinions, not findings)

1) Marketing content should proactively demonstrate how a machine enhances human agency: e.g. put controls in hands and document lay-people operating robots for the first time, allowing users to set their own objectivs or simply play; similarly document first-time users constructing a simple program with some guidance. Additionally, roboticists should be vocal about the philosophy embedded in the design, answering questions like “who made this?” “why?” “for what purpose?” early in user interactions.

2) Robot creators should produce positive fiction, becuase there is very little, which is both tragic and problematic. Collaborations or competitions involving amateur futurists (e.g. ‘best short screenplay gets to produce with your product’).

3) In general, the speculative designs inspired by fictional representations (where a robot emerges seemingly of its own accord) were received with unpredictable mixtures of amusement, and unease. Given film’s optimization for engagement, this seems a reliable trope. However, I would like to see film experiment in the opposite direction: reveals that are slow, artful, and highlight the enhancement of user agency.

I summarize some findings from qualitative responses in the video below, supplemented with some quantitative data from 2D online surveys I completed off-campus. Reactions definitely differed in-person vs online, though the added perspective was useful.

Of course, not all robot-first-encounters will happen in packaged contexts: most won’t. Most will be incidental (walking into a space with operating robots) and some will be designed deliveries (in the vein of Carvana or Tesla purchases) or pickups (like picking up a car from a dealer, or off the line at the factory). Additionally, the volume of fiction and marketing content featuring robots will increase as they become normalized as aspects of our environment. The way in which designers choose to present robots in particular contexts will shape how they do (or don’t) enter into our spaces broadly, and should reflect and encourage an appropriate relationship with and philosophical stance towards this emerging technology. While I am often amused and tempted by dramatic theatrical reveals, this process has given me cause to seek more artful, lucid, and agential first-encounters than fiction has yet imagined for us.